Lumbosacral radicular syndrome

LRS / hernia nucleus pulposus (HNP) / herniated disc / sciatica

Lumbosacral radicular syndrome (LRS) is a collective term for the pain associated with compression of a nerve root in the back. This can be associated with loss of strength, pins and needles or loss of sensation in the leg. The most common cause of lumbosacral radicular syndrome is a back hernia.

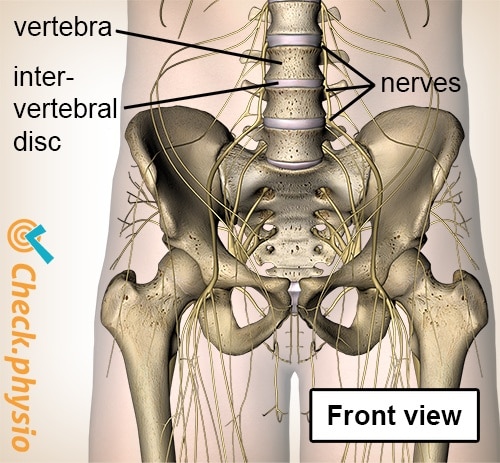

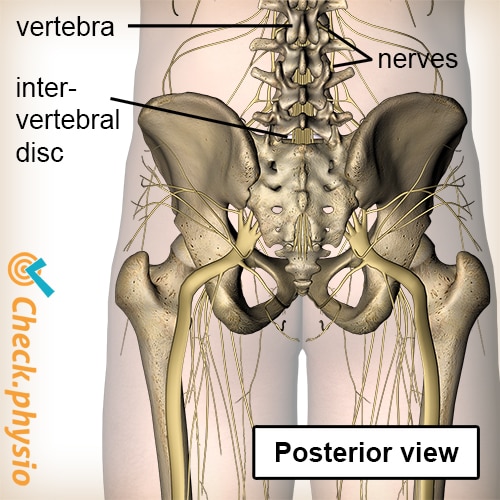

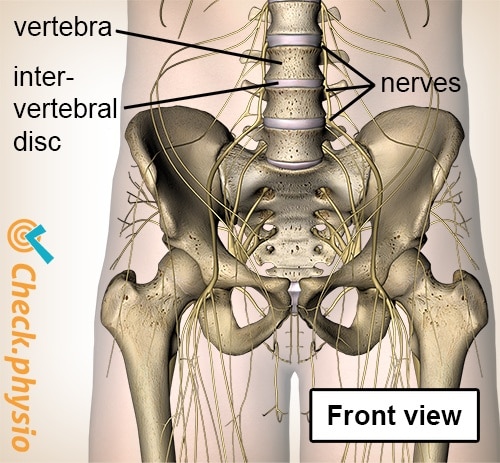

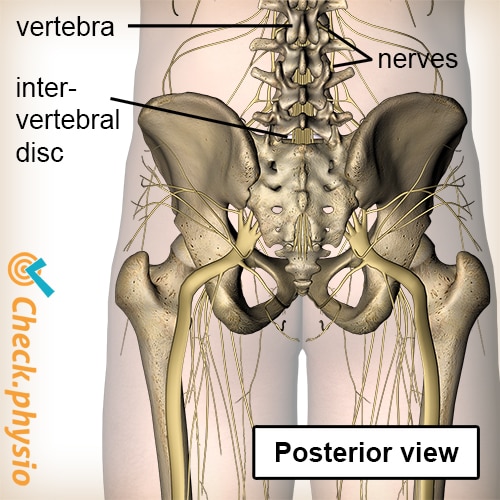

A bundle of nerves runs through the vertebrae of the back. At each vertebra, a number of nerves exit the spine in the direction of various parts of the body. Functions of the nerves include ensuring that we can control muscles and that pain signals from the entire body are passed on to the brain.

Description of the condition

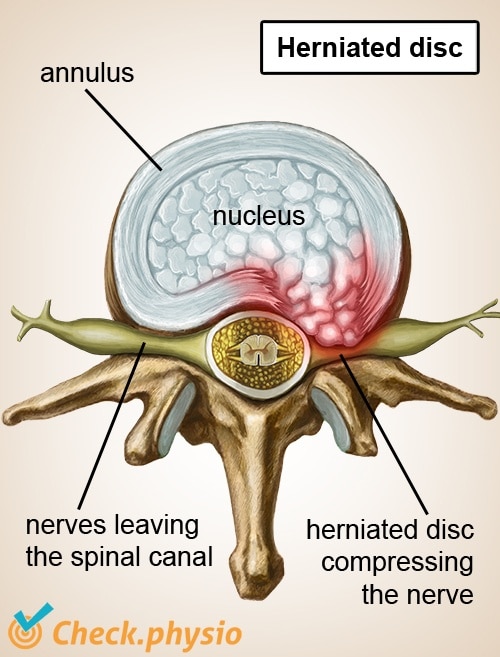

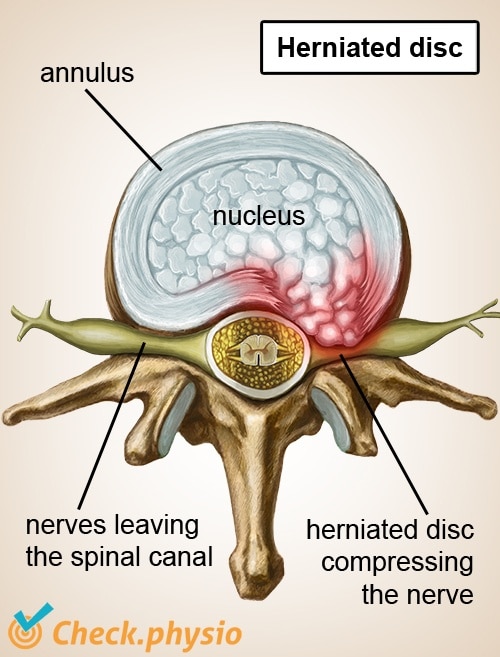

In the case of lumbosacral radicular syndrome, a nerve root becomes impinged or irritated at the site where the nerves leave the spinal canal. This can cause the nerves to pass the signals on less effectively. As lumbosacral radicular syndrome affects the nerves going to the legs, this syndrome causes problems with the legs in addition to back pain. This results in muscles being controlled less effectively (loss of strength) and can cause disrupted sensation (pain or other sensations in the leg).

Cause and origin

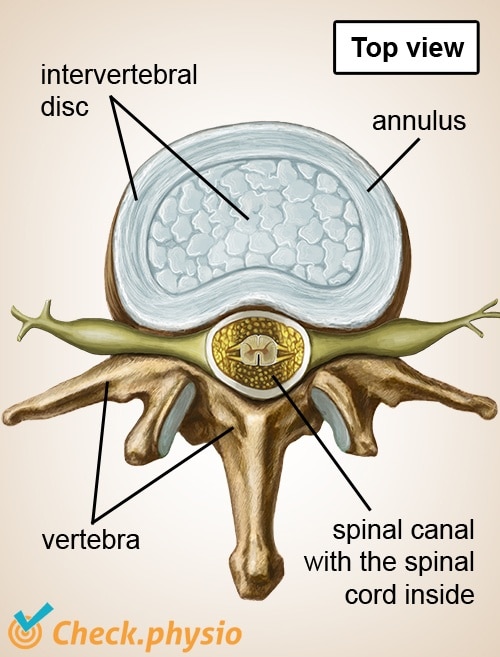

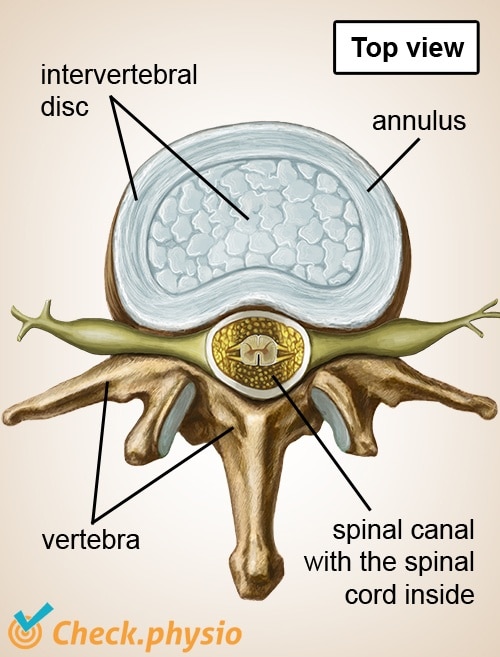

In 90 % of cases, the symptoms are caused by a herniated disc. A prolapsed (or protruding) intervertebral disc presses on the nerve, causing it to be impinged. In the case of a pure hernia, the nucleus pulposus protrudes from the intervertebral disc. This is a gel-like core, which forces its way out through the fibrous outer ring (the annulus fibrosus) of the intervertebral disc.

In some cases it is caused by a narrowing in or around the spinal canal. This can happen when a vertebra becomes deformed as a result of the ageing process, when a vertebra shifts in relation to another vertebra (spondylolisthesis), or when a vertebra breaks (compression fracture).

Sciatica and back hernia

The terms 'back hernia' and 'sciatica' are often used interchangeably. Sciatica refers to the nerve pain in the back when the sciatic nerve (nervus ischiadicus) is affected. This results in radiating pain to the leg. This nerve pain is often caused by a back hernia (protrusion of the intervertebral disc), but can also have other causes.

Signs & symptoms

- Pain in the lower back.

- The pain radiates to the leg over the course of the nerve (sciatica).

- Sometimes the pain radiates to both legs.

- Irritation, loss of sensation or a numb or cold sensation in the leg.

- Loss of strength or disrupted reflexes.

- The radiating pain can be sharp and run down to below the knee, over the lower leg and even to the foot.

- The pain in the leg is usually most prominent.

- The pain symptoms are often related to posture.

- Stretching the nerve makes the symptoms worse (straight leg raise test).

Diagnosis

An initial diagnosis is made of the symptoms based on the patient's story and the physical examination. Additional examinations using myelography (radiographic examination with contrast to locate the pathology of the spinal cord), a CT scan or an MRI will only be performed if surgery is being considered or if there are indications for another cause other than a back hernia.

Treatment

Conservative management of lumbosacral radicular syndrome is usually favourable with regards to the symptoms in the legs. However, the lower back symptoms can continue to exist to varying degrees. The treatment policy is aimed at alleviating the symptoms and waiting to see if the condition progresses favourably. Bedrest does not contribute to a faster recovery but can be helpful at times.

The physiotherapeutic treatment in the acute phase consists of providing advice about how to cope with the symptoms and stimulating movement. In addition, (non-weight-bearing) exercise therapy can be used to maintain mobility of the lower back. In the case of a hernia, it can be sensible to stretch the back (as far as the pain permits) during the first two weeks, in order to prevent further protrusion of the intervertebral disc. In a later stage, specific strength training of the trunk and leg muscles can contribute significantly to the prevention of a recurrence of the symptoms.

Surgery will only be considered in severe cases. Paralysis forms a relative reason for rapid surgery. If acute surgery is not indicated, surgeons often review after 6 weeks to see if the conservative management is effective.

Exercises

Take a look at the online exercise programme here with exercises for lumbosacral radicular syndrome.

You can check your symptoms using the online physiotherapy check or make an appointment with a physiotherapy practice in your area.

References

Cleland, J.A. & Koppenhaver, S. (2011). Netter's orthopaedic clinical examination: an evidence-based approach. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier.

Mens, J.M.A., Chavannes, A.W., Koes, B.W., Lubbers, W.J., Ostelo, R.W.J.G., Spinnewijn, W.E.M. & Kolnaar, B.G.M. (2005). NHG-standaard. Lumbosacraal radiculair syndroom. Eerste herziening. Huisarts Wet. 2005;48(4):171-8.

Nugteren, K. van & Winkel, D. (2006). Onderzoek en behandeling van lage rugklachten. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Tulder, M.W. & Koes, B.W. (2004). Evidence-based handelen bij lage rugpijn. Epidemiologie, preventie, diagnostiek, behandeling en richtlijnen. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Verhaar, J.A.N. & Linden, A.J. van der (2005). Orthopedie. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Vroomen, P.C.A.J., Krom, M.C.T.F.M. de, Wilmink, J.T., Kester, A.D.M. & Knottnerus, J.A. (2002). Diagnostic value of history and physical examination in patients suspected of lumbosacral nerve root compression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:630-634.